The Fable, a Timeless and Universal Phenomenon

The fable is probably the oldest literary form of animal anthropomorphism that exists, present in writings, but also of immense oral tradition. It appears in all cultures and societies, old and new, with a universal appeal and usefulness that never goes out of style.

The fable is a narrative composition, which may be in prose or verse, the main trait of which is that it has animal characters (or, less frequently, objects) with human attributes, such as the ability to speak or reason. Animal anthropomorphic stories.

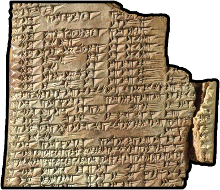

The earliest written fables we have proof of date back to ancient history, to the Mesopotamian cultures of the 23rd to the 6th century B.C. (on the Middle East), written in the ancient and extinct Akkadian language of Assyrians and Babylonians. We have fragments of these because they used cuneiform writing: on clay tablets they would leave wedge-shaped marks done with a blunt weed, hence the name cuneiform (wedge shaped). The fable of the serpent and the eagle, included in the Legend of Etana, dates back to at least the 17th century B.C. It can be seen thus that long before the furry fandom existed as we know it, and long before any generation close to us, there was a clear interest in stories and adventures starring ‘funny’ animals.

The reason why the fable has fascinated, for centuries, adults and children alike, is its allegorical quality. An allegory is a literally false description. A made-up story that is fictional, but that metaphorically represents a real situation that feels close, in which people can see themselves. Therefore, the fable creates a parallelism between our daily real lives, and that fantastic world of animals, being able to marvel or learn from them, to empathize with their situation or with their decisions.

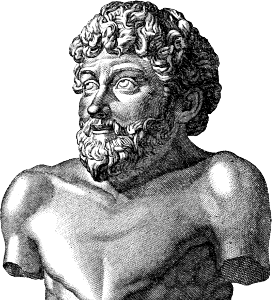

Apollonius of Tyana, a Greek philosopher from the 1st century, said to his peers talking about the fabulist Aesop:

“Fables, I believe, are more conducive to wisdom than other myths. Those who so much love poetry, that talk about heroes, outlandish passions, conflicts and crimes […] destroy the soul of those who listen; the pretense of reality leads jealous and ambitious people to imitate those stories. Aesop, on the other hand, had the wisdom, like those who dine well off the plainest dishes, to make use of humble incidents to teach great truths. […] The epic poets add violence to their false stories to make them more probable. On the other hand, Aesop, publicly recounting a story that everyone knew not to be true, told the truth. The purpose of fiction in his stories was none other than to make them useful; thereby offering teachings to its audience.” (Life of Apollonius of Tyana, by Philostratus of Athens, 2nd or 3rd century)

This is, amongst others, a reason why many writers and cartoonists, completely oblivious to trends somehow supportive of the furry fandom, have used animal anthropomorphism allegorically, as a tool to tell a story that would otherwise not have been as beautiful, or entertaining, or shocking or educational. The best known and most obvious modern work that mirrors this trend is Animal Farm, by George Orwell (1945), a political allegory written as a fable.

The fable thus has an appeal beyond literary aesthetics; also in pedagogy, ethics and rhetoric. And, it’s inevitable, following this stream of thought, to speak more in depth about the Greek Aesop, founding father and promoter of the fable in our Western culture.

Aesop was an ancient Greek from the 6th century B.C. who was captured and made a slave. Despite his acquired status as servant, as merchandise, he had the life of a scribe, a personal assistant to his owners. He had the reputation of being witty, ingenious, and telling animal stories in the process of negotiations and discussions, so as to ‘score points’ in a smart devastating manner that left his contemporaries impressed and astonished. He obtained his freedom, and later became part of the Assembly of the island of Samos, where he worked as a public speaker and lawyer, using his own fables for that purpose. He became famous to such a degree that anyone who wanted to make a good impression as a witty joker in banquets and symposiums of Athens in the 5th century had to have studied his work, or memorized those stories they were lucky enough to hear. They speak of him with respect and admiration the comic playwright Aristophanes, the philosophers Plato and Socrates, and Aristotle and his school. Some of his most well-known fables are The Fox and the Grapes (Perry Index 15), The Tortoise and the Hare (226), and The Fox and the Crow (124). Some sources cite his work being used as a textbook in ancient Greece.

Aesop’s name was so linked to ingenious animal fables, that hundreds of fables that are known or suspected to not be his, were attributed to him. The fable invariably became associated with Aesop, and he became a mythological character bigger than he was in life. To say that a story was originally told by Aesop meant receiving the immediate attention from the audience, and in some fables he appears as a character of the story. There is also a made up biography of Aesop called The Aesop Romance, an anonymous dramatized telling of his life, popular among ancient Greeks, in the same way other epic poems were at the time.

Nowadays, going to the children’s literature section at any contemporary bookshop, means finding the influence of Aesop everywhere. Most of his fables as we’ve received them finish with a moral, a lesson or teaching that is concluded from the story. However, these were added later on by their editors and collectors, and thus traditionally are printed separately from the story, or in italics. Some morals are absurd or stupid, others are educated and valuable. But we probably owe to these, the morals, that we’ve kept Aesopic fables in our popular culture.

Long before they were stories for children, fables had a rhetorical and argumentative use. Public speakers would leaf through the fables in search of anecdotes to defend their positions. For example, the Aesopic fable The Pigeon and the Painting (Perry Index 201), finishes with the sentence:

“Like the pigeon, some men, because of their strong desires, get into matters they know nothing about, falling into ruin.”

The moral could be used to deter those who, without ability nor competence, advocate their importance in matters of public interest. As in this example, fables were for many a useful tool for public speaking.

In fact, many of Aesop’s fables that are in accordance with their times, are cruel, scathing, have treachery and deceit, mockery and disdain, and show death and suffering without compassion. This is the case, among others, of The Ant and the Grasshopper (Perry Index 373). In the old version, the ant laughs at the hungry grasshopper, without pity nor remorse. Fables didn’t turn into mostly children’s literature until the 19th century. The Aesopic stories aimed at children are carefully selected, elongated and softened, so the mentioned fable doesn’t usually end up with the corpse of a grasshopper, but with an ant that’s ultimately merciful.

The use of allegories in literature had its peak in the Middle Ages, times during which Christian monks made interpretations of texts on various levels: literally, morally and spiritually. A famous rewrite of Aesop’s fables from the 12th century are the Ysopets by Marie de France, a retelling that reflects the feudal reality of the period, as well as the critical judgments of the author. The medieval fable gave rise to the Animal Epics, narrative written in verses with the adventures and misadventures of anthropomorphic animals. They’re more mischievous in nature, and satirize the weaknesses and absurdities of society. The most famous ones are from the cycle of Reynard the Fox.

Mainly from the 12th and 13th century, the cycle of Reynard the Fox (Renart, Reinhard, or equivalents), are a set of European works, from different places and in different languages (German, English, Dutch, French…), that have as their main character this anthropomorphic fox. Reynard is a witty and deceitful anti-hero whose public is nonetheless sympathetic to. His most regular enemy is his uncle Isengrim, a crude cleric wolf. These works were most famous and prolific in France, where to this day the word for “fox” is “renard”. Notably, they were a vehicle for social criticism and entertainment, not particularly aimed at children, but aimed at society in general, especially from those who were bourgeoisie. The Spanish Majorcan religious philosopher Ramon Llull included Reynard in several of his animal-anthropomorphic stories, also allegoric, in his book Llibre de les Bèsties (The Book of the Beasts) (1289). Reynard was, therefore, the furry superstar of the Middle Ages. It’s no coincidence that the movie Robin Hood by Walt Disney (1973), with a main character that’s a fox and an evil character that’s a wolf, has a resemblance to the adventures of Reynard the Fox – this medieval work was the initial inspiration for the art and the story of the film.

In the 17th century, the French Jean de La Fontaine tore the old prominence of Aesop by publishing many fables of his own and from assorted origins; twelve books in total, of increasing quality, for more than 25 years. Considered some of the best works of French literature (before Victor Hugo), he brought a renewed interest in fables to the rest of Europe as well, where compilations of fables included versions of La Fontaine, since then and until now. In Spain, in the 18th century, the writers Félix María Samaniego and Tomás de Iriarte followed suit. In later decades, other writers would use the literary structure of the fable, and animal anthropomorphism in their works, such as the famous Lewis Carroll, Kenneth Grahame, Rudyard Kipling, Hilaire Belloc, Joel Chandler Harris, and Beatrix Potter, among others.

Throughout all these works, the stereotypical personality of each anthropomorphic animal hasn’t always remained the same. Sometimes it’s even absurd compared to real documented habits we know nowadays for every species. However, this does nothing but reinforce the anthropomorphic nature of these works, since they were always meant to be a reflection of our humanity, of our customs, our passions, interactions and contradictions. As Uncle Kage says, we see in animals a reflection of ourselves. The furry is not only an aesthetic for entertainment, it’s a way to make introspection easier, to improve as human beings, and to enjoy learning.

Bibliographic references

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2013)

- The Literary History of a Mesopotamian Fable, by Ronald J. Williams; Phoenix Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer, 1956)

- The Complete Fables (Aesop), introduction by Robert Temple, translation by Olivia Temple; Penguin Classics (1998)

- Aesopica: A Series of Texts Relating to Aesop or Ascribed to Him, by B. E. Perry (1952)

- Aesopica: Aesop’s Fables in English, Latin & Greek, by Laura Gibbs (2002) (link⇒)

- Disney’s Robin Hood: A Bit More Medieval Than You Might Think, by Andrew E. Larsen (2014) (link⇒)

- “Reynard the Fox” in Animation, by Fred Patten (2013) (link⇒)

Images

- Drawings by Olven (link⇒), Janet Skiles, and Corgidoodle (link⇒)

- Cuneiform tablet of the Legend of Etana with the fable of the serpent and the eagle, British Museum K. 19530 (link 01⇒) (link 02⇒)

- Bust of Aesop, engraving from 1885 (link⇒)

- The Ant and the Grasshopper, illustration by Milo Winter (1919) (link⇒)

- Illustration of Renart le nouvel, from the 13th century (link⇒)

- Reynard the Fox, drawing by Ernest Griset (1869) (link⇒)

- Reynard the Fox, illustration on a manuscript from the 15th – 16th century, British Library, Royal 10 E IV f. 49v (link⇒)